by

No Sweat

Lindy's parents were almost fifty years old when he was born. His mother, Maybel, had a wooden leg, the results of polio. That leg had soured her on life. But when Lindy was born she changed. In him she found a certain refuge. Her life became tolerable. In him, she demanded all.

Lindy's father was a tiny man with thick glasses. He worked in a railroad office close to their home. In his spare time he was the local scoutmaster, stressing duty and honor. ln his son went all his love, all his wisdom.

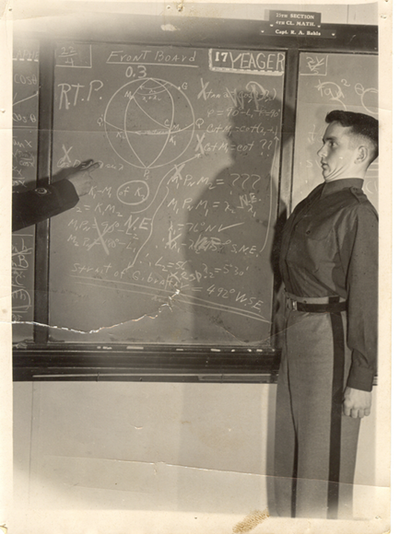

After high school, Lindy was accepted into West Point. West Point in 1951; the era of the Cold War. West Point, period; an incredible achievement from a tiny town in eastern Kentucky.

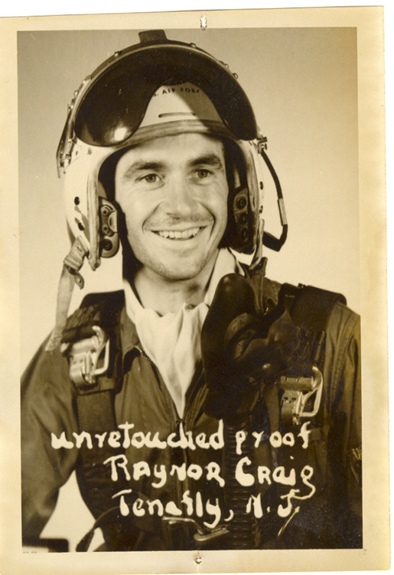

For Lindy's parents and the little town of Ravenna, Kentucky, it was a time of elation. It was pleasing to know that an especially kind person be justly rewarded. While at West Point, Lindy's father died. When Lindy graduated, he switched branches of the service. He had to support his mother and the Air Force paid more. From a flight training school in Georgia, Lindy went into S.A.C. In the next few years he became a captain of one of the most destructive bombers in the world. He also fell in love and married Audry, a girl from Iowa. As Lindy became more and more addicted to flying, to power, and to spending days of never landing, his wife and mother competed for his ground time, his love. Audry thought that if she had a child, then Lindy's flying addiction would fade. She had twins, two fine sons.

Still, it wasn’t enough. Shortly after, she took her own life.

The two babies were given to Audry's mother. She blamed Lindy for Audry's death. Lindy surrendered from the skies. The Air Force didn't want a person in control of a bomber under such psychological duress; A duress soon evolved into depression. You love literature, they reminded him. If you want to teach English at the academy, we'll hire you. First you need a Ph.D. We'll pay for any place you want to go. The pension he got, he gave to his sons and mother. Material possessions meant nothing to him.

Through it all, Lindy's mother had tried to believe that he was temporarily sick. But when she looked in the mirror she knew that things were not going to change. That everything good and glorious was gone never to return.

At home, Lindy stayed mostly in his dim lit bedroom, sitting in an old rocker next to his bed. Beneath the cracked plaster in his ceiling were relics of his past. His father’s B.S.A. Silver Beaver award, his tight-tucked, grey, wool West Point blanket, framed letters from his classmates’, generals and the men who'd walked on themoon. An old brown radio always played jazz and blues. Beneath his bed, and stacked everywhere on the floor, were novels. He could easily quote from any of them, especially Hemingway. Several years ago, on a day before Christmas, I stood by my loft, looking at Lindy’s empty home. I knew that he was in the V.A. hospital and that his mother had been placed in a rest home.

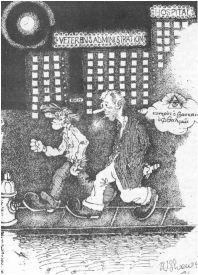

That evening, I found myself near Lindy, fetching him back home. The V.A. Hospital was a tall, stark, brick building full of forgotten, lost and tortured souls. Lindy's private cubicle was not much larger than his half bed; almost a closet. "I like it." he said, "It reminds me of the Point.” Lindy could not escape his memory of glory and then what had happened to Audry and his sons.

When he was a boy, he’d been elated to receive letters back from the soldiers in the war. Now, the great war was in him. Once, he'd jumped up on a table and led the cadets in a cheer against Navy. Once he and Audrey had bowed under so many crossed swords as rice filled the air.

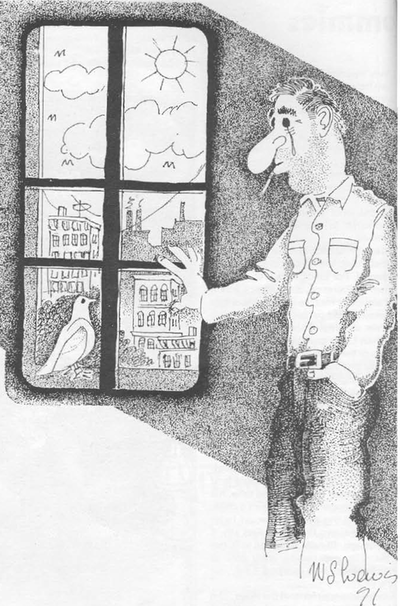

Lindy had lost a lot of weight since I’d last seen him. He seemed more nervous and grey, constantly burning a cigarette. Outside, the night owned a biting cold. And up in the sky, a full moon had two halos surrounding it. "Looks like two in a holding pattern," he said. Then he looked at me and pulled out a drink. "We'll never get out of the twentieth century," he assured. He couldn’t have been more serious, or pleased. Pausing, we noted a poor pigeon, all ruffled up and roosting alone just outside his window.

"Sometimes a racer gets lost and winds up like that,” I remarked.

Lindy stared a long time at the bird, just as he'd been doing day from his room.

I could only wonder what he was thinking.

No Sweat

Lindy's parents were almost fifty years old when he was born. His mother, Maybel, had a wooden leg, the results of polio. That leg had soured her on life. But when Lindy was born she changed. In him she found a certain refuge. Her life became tolerable. In him, she demanded all.

Lindy's father was a tiny man with thick glasses. He worked in a railroad office close to their home. In his spare time he was the local scoutmaster, stressing duty and honor. ln his son went all his love, all his wisdom.

After high school, Lindy was accepted into West Point. West Point in 1951; the era of the Cold War. West Point, period; an incredible achievement from a tiny town in eastern Kentucky.

For Lindy's parents and the little town of Ravenna, Kentucky, it was a time of elation. It was pleasing to know that an especially kind person be justly rewarded. While at West Point, Lindy's father died. When Lindy graduated, he switched branches of the service. He had to support his mother and the Air Force paid more. From a flight training school in Georgia, Lindy went into S.A.C. In the next few years he became a captain of one of the most destructive bombers in the world. He also fell in love and married Audry, a girl from Iowa. As Lindy became more and more addicted to flying, to power, and to spending days of never landing, his wife and mother competed for his ground time, his love. Audry thought that if she had a child, then Lindy's flying addiction would fade. She had twins, two fine sons.

Still, it wasn’t enough. Shortly after, she took her own life.

The two babies were given to Audry's mother. She blamed Lindy for Audry's death. Lindy surrendered from the skies. The Air Force didn't want a person in control of a bomber under such psychological duress; A duress soon evolved into depression. You love literature, they reminded him. If you want to teach English at the academy, we'll hire you. First you need a Ph.D. We'll pay for any place you want to go. The pension he got, he gave to his sons and mother. Material possessions meant nothing to him.

Through it all, Lindy's mother had tried to believe that he was temporarily sick. But when she looked in the mirror she knew that things were not going to change. That everything good and glorious was gone never to return.

At home, Lindy stayed mostly in his dim lit bedroom, sitting in an old rocker next to his bed. Beneath the cracked plaster in his ceiling were relics of his past. His father’s B.S.A. Silver Beaver award, his tight-tucked, grey, wool West Point blanket, framed letters from his classmates’, generals and the men who'd walked on themoon. An old brown radio always played jazz and blues. Beneath his bed, and stacked everywhere on the floor, were novels. He could easily quote from any of them, especially Hemingway. Several years ago, on a day before Christmas, I stood by my loft, looking at Lindy’s empty home. I knew that he was in the V.A. hospital and that his mother had been placed in a rest home.

That evening, I found myself near Lindy, fetching him back home. The V.A. Hospital was a tall, stark, brick building full of forgotten, lost and tortured souls. Lindy's private cubicle was not much larger than his half bed; almost a closet. "I like it." he said, "It reminds me of the Point.” Lindy could not escape his memory of glory and then what had happened to Audry and his sons.

When he was a boy, he’d been elated to receive letters back from the soldiers in the war. Now, the great war was in him. Once, he'd jumped up on a table and led the cadets in a cheer against Navy. Once he and Audrey had bowed under so many crossed swords as rice filled the air.

Lindy had lost a lot of weight since I’d last seen him. He seemed more nervous and grey, constantly burning a cigarette. Outside, the night owned a biting cold. And up in the sky, a full moon had two halos surrounding it. "Looks like two in a holding pattern," he said. Then he looked at me and pulled out a drink. "We'll never get out of the twentieth century," he assured. He couldn’t have been more serious, or pleased. Pausing, we noted a poor pigeon, all ruffled up and roosting alone just outside his window.

"Sometimes a racer gets lost and winds up like that,” I remarked.

Lindy stared a long time at the bird, just as he'd been doing day from his room.

I could only wonder what he was thinking.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed